Measuring Social Impact

May 1, 2019

For our latest Q&A on sustainability we spoke with Howard W. Buffett, who is approaching the issue from academia, as well as the private sector. He recently co-authored a book, Social Value Investing, with his fellow Columbia University professor William B. Eimicke. Howard sits on the North America advisory board for Toyota Motors, and previously served in the White House and the Department of Defense.

This is an interview with Howard W. Buffett. NYSE presents the information for informational purposes, but does not endorse, represent nor warrant the accuracy of the narrative, which relies solely on material provided by Howard W. Buffett.

The material in this interview is copyright Howard W. Buffett. Social Value Investing, Impact Rate of Return, and iRR are federally registered trademarks of Global Impact LLC and all rights are reserved. This material is used with the express permission of Global Impact LLC/Howard W. Buffett.

You have worked at senior levels in government, philanthropy, and the private sector. What are some commonalities you see in how leaders try to achieve positive impact?

This is a key research question I have been focused on over the past seven years while teaching at Columbia's School of International and Public Affairs. During this time, my team and I have spoken with corporate executives, government officials, and philanthropists around the world. We have researched how some of the most respected leaders from all sectors approach planning, management, and measurement for achieving success in their organizations.

Early on, we discovered a trend that fascinated us. Many of these leaders had engaged in cross-sector partnerships (a successor to public-private partnerships), but they lacked tools to measure their success. No matter how confident they were about a given partnership's results, they struggled to prove it. In part, this is because they did not have a common framework for tracking and analyzing the impact of their collaborations with others.

So we set out to explore this issue more deeply by understanding the questions, challenges, and approaches these leaders had previously taken to measure success, and then applying those insights to cross-sector partnerships and especially towards tracking outcomes like social and environmental impact.

We found that serious attention has already been dedicated to measuring the impact of certain practices in corporate settings. However, many executives were seeking guidance on ways they could effectively partner with others to serve their interests and society's interests at the same time. Whether through corporate social responsibility, sustainable or impact investing, or more stakeholder-centric company policies, corporations of all types are shifting their ways of doing business and considering broader community- and societal-level consequences of their work.

Seven years later, our findings show that corporate executives can bring benefits to their companies through effective partnership with public officials, nonprofit managers, foundation heads, and community leaders. In part, this is because non-corporate partners are largely “free from profit-making incentives and constraints”, and because they seek benefits for society in the form of positive externalities. But to collaborate well across sectors, leaders need a common framework that can help align activities and incentives even when organizations are driven by different end results.

We have translated the findings from our research, observations, and discussions into a book published by Columbia University Press last May, titled Social Value Investing: A Management Framework For Effective Partnerships. The methodology we outline draws from some principles of value investing—namely, the use of long-term investment strategies to unlock hidden or intrinsic value—and it is inspired by the success and structure of Berkshire Hathaway's management approach.

One of our key research topics, for example, is how to bring diverse teams together to solve problems in a way that's more effective, comprehensive, and accountable to the needs of society. We found that when the leaders of partnering organizations adopt a collaborative and intentional mindset, work to identify commonalities across teams, and focus on mutual long-term objectives, they are far more likely to succeed.

In the book we detail five key components of the Social Value Investing management framework and explore a variety of successful implementation cases. Across the material, we include tools, resources, and tactics for executives to:

- Develop comprehensive and fully-integrated partnership strategies;

- Emphasize collaborative leadership through diverse and decentralized team management;

- Establish permanent or long-term co-ownership of outcomes among a partnership's and community's stakeholders;

- Deploy a blend of innovative investments, from across partners, to offset risks and achieve greater scale; and,

- Determine mutual measures of success for program and partnership performance, and track and report positive social and/or environmental impact.

The final point regarding impact tracking and reporting may seem the most obvious, but it is also the most daunting for private sector leaders. This isn't helped by the proliferation of impact reporting standards and measurement methodologies available in the market today. However, we have found that once companies have a solid understanding of the desired social or environmental impact they hope to achieve, charting a course becomes much easier—our case studies show how that's possible.

Overall, we believe that Social Value Investing serves as a guide for leaders hoping to accomplish more by aligning their priorities with the goals of partnering organizations and the communities in which they operate. And at the same time, we explain that such collaboration is an opportunity for companies to demonstrate ways in which business efficiency and customer focus can benefit the efforts of the public and philanthropic sectors as well.

As you’re working with organizations on their impact strategies, or even on specific projects, what types of metrics are you looking for?

Deciding which impact metrics matter most to each partner is a collaborative process in its own right. We begin with deliberate discussions to first understand each organization’s social or environmental goals. And if they don’t have goals articulated, we examine their past activities to determine some baselines across a few themes or categories of impact, and then mutually establish realistic objectives. Having these themes and objectives can then guide the rest of the process.

To begin, we identify a few key metrics that are usually decided on by the company, foundation, or government entity, rather than externally driven. In the corporate world, we think it is important to look for metrics that are also connected to the core operations of the business. It is ideal if we can utilize measures that are tied to social or environmental good that also make good business sense to track and monitor, especially in terms of cost or risk reduction—in other words, ones that are financially material. For example, a food company may consider basic factors such as water use, or more advanced measures, such as supply chain resiliency or product origination improvement. In our book, I give an example of a mixed-use commercial real estate development project. There, a company may consider factors such as the sustainability of building materials, overall energy efficiency, or proximity to public transportation.

As we conduct more research and further refine our understanding of the business value of social and environmental sustainability, we will see an expansion of the types of metrics businesses consider to be tied to their bottom line—especially as business leaders continue thinking and acting with longer-term time horizons in mind. That said, an important consideration is that companies not overburden themselves with impact tracking that is not strategic; they need to avoid metrics-for-metrics-sake. As we’ve seen with the emergence of numerous methods, measures, and standards, such as ESG, SASB, IRIS, GRI, and others, business executives can choose from a wide array of metrics. However, we are currently at risk of third-party survey and metric fatigue, which is why companies need to take a more active role in deciding what measures make the most sense and then commit to tracking and reporting on those in a consistent, transparent, and verifiable manner. Beyond that, just as important as what gets measured is how those metrics are analyzed and integrated into management decision making. Measurement purely for the sake of data gathering can be harmful to the bottom line, strain other resources, and get in the way of the impactful outcomes an organization is seeking to achieve. So, putting rigor and discipline around impact analysis is absolutely critical.

That’s a good segue to your academic work in this area. You’ve developed a model that helps philanthropists and investors determine where they will get the most social impact per dollar spent: Impact Rate of Return, or iRR. Why was this needed?

Let’s begin with an obvious statement: making an “impact” means something different to everyone. When someone sets out to define impact, it could be any positive change that a given individual or organization hopes to see in the world as a result of their actions. The possibilities coming from that are almost infinitely vast, which is important to recognize. As a result, determining whether or not you’re having an impact begins with intentionality and discrete goal setting.

This puts the notion of impact measurement in a new light. Impact is inherently personal and place-based, and outside organizations shouldn’t necessarily stipulate what to track. Within a set of broadly accepted norms, those best positioned to determine the specific impact they are seeking to achieve are the organizations and communities most directly affected.

To put our methodology into perspective, I’ll begin by discussing one of today’s more broadly applicable approaches, which is the practice of monetizing social and environmental outputs. For those who are unfamiliar, monetizing impact attempts to address the following: in order to calculate a social return on investment, what is the monetary value one can assign to a given program’s or investment’s social or environmental outputs? For example, monetization may be used to calculate the value to society of a gallon of water preserved, a successful job placement, or a low-income student graduating from high school who otherwise wouldn’t. The approach has been around for decades, but received recent attention when TPG’s Rise Fund stated it would be monetizing impact measures across its $2 billion of investments.

One drawback to monetizing impact is that it attempts to use a universal unit (a dollar) as an absolute measure in a context where impact is nearly the exact opposite—something relative. Consider that five people each giving away $100 to improve the world would almost invariably find five very different ways of doing so, each driven by their personal life experiences, hardships, or hopes. It is also likely each of those individuals value $100 differently, depending on their financial circumstances. Further, a person’s perspective on what constitutes good or bad quality impact will be driven by their individual preferences and priorities, making an absolute measure all the more difficult.

This is where Impact Rate of Return comes at things a bit differently, because it is based on relative analysis. Unlike monetization, the iRR methodology seeks to address the following: when given a variety of investments or programs to choose from, which option will yield your greatest impact rate of return per dollar invested? If you can think of monetization as estimating the dollar value of impact, our approach works to calculate the impact value of each dollar. With this calculation in place, an investor or grant maker is able to judge which opportunity will be most effective at accomplishing their impact goals. iRR incorporates flexibility around investor or grant maker preferences, but it does so while maintaining a standardized framework. This flexibility also allows for community and stakeholder preferences to be integrated into this analysis as well.

I should clarify that I’m not saying monetization of outputs is a bad or obsolete practice. Quite the opposite, actually, as I believe monetizing social and environmental measures will continue to serve an incredibly important role in the shifting landscape of private-sector engagement. For example, monetizing outputs helps to make a clearer business case for conservation, workforce retention, or other socially beneficial programs that may have been overlooked in the past. In this way, it is helping corporations to act in a more socially responsible manner, especially in the face of short-termism or shareholder activism. It is also, to date, one of the most easily understood and communicated ways to assign a tangible value to activities with a positive impact. Beyond this approach, though, iRR provides a consistent yet flexible model where an investor can decide which measures matter the most, and go beyond just measuring outputs, but also analyzing their metrics for a better understanding of what impact means within the context of their activities.

What are the key inputs into the iRR model?

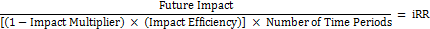

I’ll start by explaining that Impact Rate of Return is derived from a formula modeled after the calculation for Net Present Value. In the same fashion that NPV calculates the time value of money, iRR calculates the impact value of money. Therefore, the two formulas’ inputs mirror each other to a certain degree.

The iRR formula divides future (or expected) impact from an investment by the effectiveness and quality of that impact over time, resulting in its potential rate of impact. In order to do this, iRR is calculated as:

Once setup, organizations use the formula and its inputs as a foundation from which to track, analyze, and report on actual impact achieved during a given time. It also indicates where certain aspects of an investment or program may be under- or over-performing.

Before computing these variables, and before I go into more detail on each, a number of attributes relevant to the intended impact must be decided upon. First, organizations identify a single, clearly defined and straightforward metric directly tied to their social or environmental impact goals (we call this the Key Impact Indicator). For example, this unit may be the number of square feet developed for a sustainable real estate project, acres of farmland for environmentally friendly food production, or the megawatt hours generated by a solar power energy investment. In short, the greater the number of Key Impact Indicator units, the greater the potential scale of social or environmental impact delivered by the program.

Second, organizations establish an overall impact goal for their work in terms of their Key Impact Indicator. This creates a comparative baseline for any programs evaluated before an investment or allocation is made. As one example, a real estate firm may establish an overall goal of developing 3,000,000 square feet of new buildout, or in the solar example, to generate 150 MW of energy sustainably.

Finally, organizations need to settle on a uniform scale of qualifications or attributes in order to evaluate the quality of impact being delivered. This scale could be an internally developed scorecard or an existing industry standard. In some cases this is fairly straightforward; in the real estate development example I gave, a good proxy for impact quality is LEED Certification. For environmentally friendly food production, as another example, investors or project managers may utilize the Sustainable Agriculture SAN Standard as their rating framework. This aspect of the methodology makes it incredibly flexible because it allows the formula to be customized to an organization’s specific preferences.

With these attributes established, we can calculate the following inputs for the formula:

- Future Impact: to estimate an investment’s Future Impact, we calculate the percentage of an organization’s impact goal that investment is expected to achieve.

- Impact Multiplier: an investment’s Impact Multiplier is its rating based on the scale of quality determined by the organization. The higher the rating, or quality of impact delivery, the higher the multiplier value. We generally recommend scorecards or existing standards that lend themselves to multi-attribute utility theory, in order to facilitate detailed customization.

- Impact Efficiency: an investment’s Impact Efficiency is a measure of dollars expended per Key Impact Indicator unit delivered; however, due to the dramatic variance in cost per unit across different types of impact, we apply a standard logarithmic function to this figure.

- Number of Time Periods: this is the amount of time involved in the life of the project or investment, usually expressed in years.

I go into further detail on the iRR methodology in Chapter 12 of Social Value Investing, providing a variety of use cases and example calculations, as well as a discussion about the model’s advantages and disadvantages.

Of course, there is a lot more that we could go into here—as I mentioned, I’ve spent the last several years on this—but I’ll end with one final note that should be helpful. There is a consensus emerging among the leaders we’ve spoken with that combining impact returns with business objectives will keep everyone focused on quality of impact. Philanthropies can use iRR to measure their portfolio of grants or program-related investments as well, but in cases where profitability is a consideration, the iRR analysis can easily be combined with traditional financial analysis. For example, investors often set an expected internal rate of return at the outset of their investments and track their returns over the years; similarly, they can do the same with their impact goals by using iRR. In this way, the iRR model combines goals for financial return with discrete goals to improve society, which is useful for businesses placing increasing importance on the active pursuit of positive impact for society.

The material in this interview is copyright Howard W. Buffett. Social Value Investing, Impact Rate of Return, and iRR are federally registered trademarks of Global Impact LLC and all rights are reserved.